The world-famous Ware Collection of Glass Models of Plants includes a very tempting glass banana – and hundreds of amazing glass flowers, all made by hand.

“I’ll meet you at the giant moa,” Blue Magruder said. That’s the landmark when you’re at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, looking for The Glass Flowers gallery.

Back when I actually lived in Boston, I’d heard about them. Handmade by mere mortals more than a century ago. But nothing, no matter what I read or saw on paper or computer screen, came close to the real thing.

Created for botanists

Or the real fake things, as it were. Because the Glass Flowers are accurate models of plants and their parts, created for yesterday’s botanists – and admired today as works of fine art. Blue Magruder, the museum’s director of communications and marketing, walked me past the giant moa skeleton into a dark climate-controlled room filled with rows of classic 19th-century wooden display cabinets.

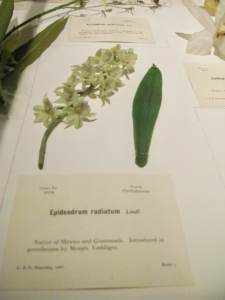

We started with the first flower – model 1 of the collection. An amazingly real orchid (or, to be more scientific, the epidendrum radiatum) that looked freshly plucked and gently laid into the display. Wow. “Oh, but this is just the first one,” said Blue. “They got better after this.”

She wasn’t just referring to the flowers – Blue also meant the skills of Leopold Blaschka and his son, Rudolf. In the days of Asa Gray and Darwin, plant-hunting expeditions resulted in browning specimens, dried flat for preservation. When Prof. George Lincoln Goodale of Harvard was asked to create the Botanical Museum, he sighed and took a stroll through the enviable collection of the Museum of Contemporary Zoology.

Glass creatures of the sea

Their collection of glass replicas of the invertebrate creatures of the sea were so beautiful – and solved the same issues he faced, of preserving the transitory structure and color of life so delicate, it defied preservation. If jellyfish and anemones could be recreated with such accuracy, why not plants and flowers?

Goodale paid his first visit to the Blaschkas’ Dresden home and workshop in 1886. By 1890, the Blaschkas had been enticed to give up their lucrative worldwide business in invertebrate models. And for the next 50 years, they dedicate their lives to studies of botany.

At the museum, one display case features scarlet maple leaves as real as the ones I had passed outside. And the yellow banana! Rudolf must have seen it in person during his botanical expedition to Jamaica in 1892. He’d recently developed a taste for what was then a relatively new and exotically sweet hybrid. Shipped north by Boston Fruit Company steamships, these delicacies were eaten by knife and fork – perhaps that’s why Rudolf’s model was cut in half, and not peeled back like the common fruit we eat today.

Steady hands and hot flames

Rudolf was the fifth generation of Blaschka glassmakers, and inherited the steady hand of his forefathers. Who else, Blue explained, could have made these models. Father and son worked at a small wooden table, softening glass with hot flames so they could press, pick and pinch it into everything from small hairy root systems to translucent petals.

It all looks so real, it’s easy to just walk past that branch of figs and leaves without noticing the skillfulness required. The school kids just dashed through the exhibition, only stopping to fill in scavenger hunt lists for science class. We grown-ups lingered longer, as the closer we looked the better we realized what we were actually seeing.

“Please don’t lean on the displays,” Blue said to visitors who strolled too carelessly around one of Harvard’s most valued collections. “The flowers are incredibly fragile,” she explained. “And the glues the Blaschkas used were not as long-lasting as those we have today.”

Flowers, grasses – seeds, roots

The Glass Flowers consist of close to 4200 Blaschka works – all botanically accurate models of flowers, grasses, cacti, seeds, roots, and super magnifications that turned miniscule pistils and dissected ovaries into strangely unearthly art.

Because they are so fragile, the flowers very rarely travel. But as the British couple who eavesdropped on my tour with Blue said, this collection is one of the highlights of any trip to Boston. Luckily, they had stumbled upon it by chance in their tour guide – and somehow managed to keep from leaning on the glass.

“When I showed this to one man,” Blue said, pointing to a magnificent magnification of the flower of an ordinary clump of grass, “he said he could never mow his lawn again.”

————

The Harvard Museum of Natural History is located at 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts (USA), just past Harvard Yard.

Books:

The Glass Flowers at Harvard – the history of the flowers with exclusive photos by Hillel Burger

Drawings upon Nature: Studies for the Blaschkas’ Glass Models – the actual botanical drawings made by Leopold and Rudolf (including those made on his 1892 Jamaica expedition).